Every

year, nearly 2.5 million people go under the knife unnecessarily,

often with devastating consequences. Make sure you're not one

of them.

Due

to the power and corrupting influence of Big

Pharma, the teaching

of nutritional science and the use of vitamin and herbal supplements

is

not taught to any significant extent in our medical schools. The

obvious

reason is that teaching this science reduces the use of prescription

drugs.

Two years ago, when Leah Coppersmith went in for back surgery,

she expected to be lacing up her running shoes within days. She's

been in pain ever since.

A car accident in 1991 left this mother of four with nagging lower-back

pain--annoying, but not bad enough to keep her from running 5-Ks.

But in 2005, the nag grew to a scream.

An MRI revealed that two disks -- the gel-filled cushions between

the vertebrae -- were badly worn. Coppersmith expected the doctor

to recommend a diskectomy, in which part of a troublesome disk

is removed to relieve pressure on the nerve; the low-risk surgery

had helped her once before. But this time, the surgeon wanted

to replace a disk with an artificial one. The procedure was getting

great results, he said. Coppersmith was skeptical until he told

her she'd be back running 5-Ks again in no time. She laughs bitterly

at the memory.

Pain is now the defining feature of her life. She can't sit down

to family dinners. She quit her job because she can't work at

a desk. Her misery has company: While looking for help online,

she found a study showing that 64% of people who received the

disk, called the Charité, still needed narcotic painkillers

2 years after surgery.

Every year, upward of 15 million Americans go under the knife

-- and for most of them, surgery provides relief or a new lease

on life. Joints are replaced, organs are transplanted, lives are

saved. But Congress has estimated that surgeons perform 2.4 million

unnecessary surgeries a year in the United States, with a cost

of roughly $3.9 billion--and a toll of about 11,900 deaths. The

reason isn't simple.

"The majority of surgeons who perform these procedures are

actually very enthusiastic about their benefits," says Mark

Chassin, MD, chair of the department of health policy at Mount

Sinai School of Medicine. "It's not like they get up in the

morning and ask themselves, How many unnecessary procedures can

I do today? But there's a lot of financial incentive to do surgery

that may not benefit the patient, and very little oversight."

So how do you know when someone is suggesting surgery you don't

need -- and what can you do to prevent it? Your first line of

defense is to become your own advocate. One study showed that

when patients and doctors share the decision making, rates of

surgery drop by as much as 44%. Here, we explain what's behind

four of the procedures most often done unnecessarily and give

you expert advice on the best alternatives.

BE SKEPTICAL: SPINAL SURGERY

The waiting room of Charles Rosen, MD, a spinal surgeon and an

associate professor of orthopedic surgery at the University of

California, Irvine, was filled with patients who, like Coppersmith,

had failed disk implants. "In my 20 years of orthopedics,

I'd never seen so many people in such a severe state of constant

pain," he says. So Rosen examined the evidence backing the

Charité disk. He was shocked to see that the researchers

had compared patients who got the disk with those who received

a type of fusion surgery with a particularly high failure rate

-- 60%. (Even before the study's publication, that procedure had

been largely abandoned.) Then he discovered that researchers on

other Chariti studies were paid consultants for the device maker.

Outraged, Rosen founded the Association of Ethical Spine Surgeons.

Members agree not to take money from device makers or form partnerships

with the companies.

The spine is ground zero for unnecessary surgeries partly because

back pain is incredibly common and notoriously tough to treat.

More than 1 million sufferers opt for surgery each year, and spinal

fusion -- the use of bone grafts, screws, and other devices to

secure one or more vertebrae -- is one of the most popular choices.

Between 1996 and 2001, the number of spinal fusions skyrocketed

113%, while the number of knee- and hip-replacement surgeries

rose just 15% and 13%, respectively. But unlike those procedures,

spinal surgeries often fail -- instead of relieving pain, they

can turn it into agony. According to Aaron Filler, MD, PhD, director

of the Peripheral Nerve Surgery Program, Institute for Spinal

Disorders, at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, there

are tremendous rewards for spinal surgeons who do aggressive procedures:

Because of the hardware involved, an operation on the spine can

pay a surgeon 10 times as much as one on the brain. Yet the moneymaking

back surgeries help in only a small proportion of cases. What's

more, back surgeons are rarely held accountable if the operation

fails. "The referring doctor has low expectations,"

Filler says. "So does the patient, because everyone thinks

of back problems as so difficult to treat."

Protect Yourself

Pinpoint the pain: If your doctor labels your back pain as "nonspecific,"

it means he doesn't know the cause; if he suggests surgery, alarm

bells should go off, says Filler. Spinal fusion is most beneficial

when vertebrae slip out of place and press on the ones below,

which is easily detected on an x-ray. "When properly done

for the right reasons, spinal surgery can be extremely effective,"

says Filler.

Make lifestyle adjustments: A 2003 study compared spinal fusion

surgery with a lifestyle approach to back pain: Docs taught patients

how to protect their backs, by bending at the knees when lifting,

for instance. They also encouraged exercise, like water aerobics.

A year later, the nonsurgical approach reduced pain and increased

mobility just as much as surgery did. Alternative treatments such

as chiropractic and acupuncture can also pay off, studies show.

For more info on finding alternative treatments, go to prevention.com/links.

Consider a helpful shot: A nerve-blocking injection called an

epidural, given by a surgeon or a rehab specialist like a physiatrist,

may quiet the pain for up to a year; it helps in about 50% of

patients.

Skip the hardware: If surgery seems like the right approach, get

the simplest procedure possible. There's a much smaller chance

of complications if you have a diskectomy, for example, than if

you have an artificial disk implanted.

BE SKEPTICAL: HYSTERECTOMY

Lori Jo Vest was 36 when three doctors told her a hysterectomy

was the only fix for her heavy bleeding caused by uterine fibroids.

Terrified that she'd be thrust into early menopause--in half of

all hysterectomies, surgeons end up removing the ovaries, too--Vest

went online and discovered myomectomy, in which the surgeon cuts

out the fibroids, sparing the uterus. But her doctors nixed the

idea; after all, they said, Vest, who had a toddler, didn't want

more children. Then Vest called the nearby University of Michigan,

Ann Arbor--and nearly leaped through the phone when she heard

they had a clinic for women seeking alternatives to hysterectomy.

"The doctor said I was a perfect candidate for myomectomy,"

Vest says. She also told Vest that many surgeons dislike the surgery

because it's more difficult than a hysterectomy. Now 44, Vest

no longer is troubled by heavy bleeding, but she still has her

uterus and ovaries. *"I don't want to go through menopause

until my body is ready," she says.

Hysterectomy is second only to C-section as the most common surgery

performed on women in the United States. Each year more than 600,000

Americans have the procedure--twice the rate as in England. A

2000 study found that 70% of the hysterectomies performed in nine

Southern California managed-care organizations were recommended

inappropriately. "The most common mistake we saw was that

doctors didn't try safer, less-invasive approaches first,"

says lead author Michael Broder, MD, an assistant professor of

obstetrics and gynecology at UCLA's David Geffen School of Medicine.

Hysterectomy can be warranted if a woman has cancer, and it can

be the right choice in other cases, too--for instance, if medical

treatment didn't get your bleeding under adequate control, and

you don't want to try a surgery like myomectomy because of the

risk of recurrence. But unless you have cancer, "having a

doctor say, 'You absolutely need a hysterectomy,' is akin to a

waiter at a restaurant saying, 'You've got to have the steak,'"

says Malcolm G. Munro, MD, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology

at UCLA. "A good doctor should give you a menu of choices."

Protect Yourself

Try hormones or drugs first: Most hysterectomies are done on women

under age 45, but if you can manage symptoms of fibroids with

medication until menopause, symptoms usually ease naturally. Birth

control pills or other drugs help control irregular bleeding.

Also check into getting a progestin-releasing IUD (Mirena): It

can dramatically decrease bleeding caused by fibroids.

Consider a less drastic procedure: Like myomectomy, uterine fibroid

embolization (UFE) preserves the uterus: An "interventional"

radiologist carefully closes off blood vessels feeding the fibroids,

starving them. A woman may need more treatment after either procedure

if the fibroids come back, and both cause a fair amount of discomfort.

(UFE can require serious pain meds, although recovery is quicker

than after a hysterectomy, and the risks are lower.) For more

info on hysterectomy alternatives, go to prevention.com/links.

BE SKEPTICAL: ANGIOPLASTY

When Irwin Melnicoff, a forensic engineer in Boynton Beach, FL,

felt a stabbing chest pain at age 45, he went straight to the

cardiologist. The diagnosis? A narrowed artery. The answer? Angioplasty.

But Melnicoff was scared of surgery; even when the doctor told

him he'd die without the artery-opening procedure, he chose drug

therapy instead. (He also chose a new doctor.) That was 25 years

ago. With the help of daily heart medications, his chest pain

vanished. He walks 30 minutes a day, 7 days a week, and feels

great.

He made the right choice. Though angioplasty has been hailed by

some as a wonder fix for decades, it now turns out that most of

the time, the procedure doesn't help. Angioplasty can save your

life if it's done during or right after a heart attack. But in

other circumstances, it may not do you much good.

"Doctors used to think of heart disease as a plumbing problem--that

arteries were like drainpipes gradually being clogged by plaque

made up mostly of cholesterol," says Arthur Agatston, MD,

a preventive cardiologist and author of The South Beach Heart

Program. So it seemed to make sense to use angioplasty, in which

a small balloon is inflated in the artery, to get that gunk out

of the way by squashing it against the vessel wall. However, research

has since shown that problematic plaque actually forms within

the delicate inner lining of artery walls.

What does cause a heart attack? If the plaque within the wall

ruptures, it injures the artery, producing a blood clot as part

of the healing process. Unfortunately, the clot can close off

the entire artery--that's a heart attack, and you need angioplasty

or bypass surgery immediately. If you have angioplasty, the doctor

may also insert a stent, a mesh scaffolding, to hold open the

artery.

But if you're not having a heart attack, angioplasty (with or

without a stent) won't help and may even do some harm. That's

the news from a large trial published in April in the New England

Journal of Medicine. People with "stable" heart disease--they

weren't having a heart attack, but a vessel was at least 70% closed--fared

no worse if they received medical therapy, such as aspirin, blood

thinners, and cholesterol-lowering drugs, than if they got angioplasty.

During the next 4 1/2 years, neither group was more likely to

have a heart attack or stroke or die.

A study published late last year helps pinpoint exactly when it's

worth getting angioplasty. That trial showed that if the procedure

was done 3 or more days after a heart attack, it didn't help.

"We were very surprised--we thought angioplasty would be

beneficial even if it was done later," says lead author Judith

Hochman, MD, director of the cardiovascular clinical research

center at New York University School of Medicine. "But that's

why we do studies: to see if the patient really does benefit."

Protect Yourself

Insist on being convinced: If your doctor says you need a non-emergency

angioplasty, ask if it will prolong your life. "That question

puts a cardiologist on the spot," says Agatston. If the procedure

isn't needed to save your life, it still may make sense if angina

(bouts of chest discomfort caused by a lack of blood flow to the

heart) interferes with daily activities. But get a second opinion--from

a preventive cardiologist, not a cardiac surgeon.

Eat right, exercise, and lose weight if necessary: You needn't

avoid fats and carbs to keep your heart healthy--just choose wisely.

A diet high in omega-3-rich canola and olive oils can actually

protect your heart. High-fiber carbs in whole grains, fruits,

and veggies also help get fats out of your blood.

Use the meds known to save lives: Many people with high cholesterol

aren't on statins, though the drugs slash the risk of heart attack

by more than 30%. Similarly, most people with high blood pressure

don't get adequate treatment, studies show. Lifestyle changes

can bring down both cholesterol and BP, but if they're not enough,

medication can be lifesaving. Your doctor may also put you on

daily aspirin or another drug to lower the risk of a blood clot.

BE SKEPTICAL: KNEE ARTHROSCOPY

Soon after Diana Aceti turned 50, the ache in her knee began to

keep her from walking and playing tennis, two activities she loved.

An orthopedist said that she had a small tear in her cartilage

and recommended arthroscopic surgery. "He said I'd back on

my feet in a few weeks," says the public relations director

from Bridgehampton, NY.

But afterward, Aceti's knee hurt worse than ever. So she got a

second opinion--and the news wasn't good. In a rare complication,

her cartilage was damaged beyond repair, and she needed a partial

knee replacement. "Doctors talk about surgery like it's getting

your teeth cleaned," says Aceti. "If he'd told me this

was a possibility, I never would have done it."

Knee arthroscopy is most often used for people, like Aceti, who

have osteoarthritis--cartilage damaged by wear and tear. A surgeon

makes small incisions and inserts instruments to remove tissue

fragments and wash out the joint in the hopes of reducing pain.

Yet in 2002, when knee arthroscopy was put to the test in a randomized,

controlled trial, it failed royally. Osteoarthritis patients given

arthroscopy reported no more improvement than those who got sham

surgery--incisions were made but no arthroscope was inserted.

Still, 5 years later, the procedure remains among the top 10 outpatient

surgeries: More than 650,000 knee arthroscopies are performed

annually.

Critics say that almost everyone has small tears in their knee

cartilage visible on MRIs, providing a never-fail excuse for surgery.

"Patients have arthroscopy for what is clearly the result

of a bruise or a bump," says Ronald Grelsamer, MD, an associate

professor of orthopedic surgery at Mount Sinai Medical Center

in New York City. "For many orthopedists it's the only way

left to make a half-decent living. Does that justify it? No."

The procedure can help in certain situations, Grelsamer says:

If a piece of cartilage is catching, like a hangnail, clipping

it can make you feel better. And some doctors still believe that

for some osteoarthritis patients, flushing the interior of the

knee during arthroscopy can ease pain, perhaps by getting rid

of irritating chemicals. Researchers can't predict who will benefit

from a washout, though--and surgeon Bruce J. Moseley, MD, who

led the sham surgery comparison, argues that any improvement in

arthritis patients is due to the placebo effect.

Protect Yourself

Wait a while: Arthroscopy is most frequently done after a twist

or fall, but those injuries often get better within a few months

with physical therapy, anti-inflammatory meds, a cortisone injection--or

just the passage of time.

Be skeptical of MRI results: Arthroscopy is most apt to help if

there's a detached fragment of cartilage or a severe tear--a 3

on a 1-to-3 scale, as rated by a radiologist. But even a bad tear

may not cause pain, so ask whether it matches up with the area

that hurts. --

Extra Testosterone ... Could Mean

An Alpha Decision-Maker Type

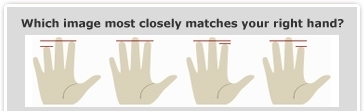

Look for a long fourth finger.

If your significant other's ring finger is longer than

his or her index finger, it's an indication that he or

she was exposed to higher than average amounts of

testosterone in the womb, says Dr. John T. Manning of

Rutgers University in his book 'Digit Ratio.' This correlates

to a personality type , which tends to be logical, decisive,

and ambitious. Thus the testosterone exposure influences

your personality and subsequently who you love.

Alcohol Awareness

7 Best Bread Brands

9 Tips To Lower Blood Sugar

Dieterata: The Inner-Clean Diet

Use Baking Soda For Your Health

Malnutrition Causes Most Diseases

9 Facts Food Makers Hide From You

7 Surprising Signs of An Unhealthy Heart

10 Ways You Can Prevent A Hearth Attack

11 Banned Ingredients Still Allowed In U.S.

7 Things Your Hands Say About Your Health

Helpful Health Hints

Pages And Points To Ponder

American

Crisis: The Military-Industrial Complex

Your Health By DaSign

Your Health By DaSign  Other Views

Other Views

Cleansing

Diet

Cleansing

Diet  Meatless Is Better

Meatless Is Better