This

article is based on the book:

The Lexus and the Olive Tree

By Thomas L. Friedman

The

Big Idea

Pulitzer Prize winning journalist Thomas L. Friedman, writes in

his book, The Lexus and the Olive Tree, about the phenomenon of

globalization and how it has instituted an international system

that has replaced the Cold War. It is a system that has united

the fates of peoples all over the world from Brazilian Indians

to Thai bankers to multinational company executives. Here, Friedman

explains how the democratization of information, technology and

finance has shrunk the world into an over connected community

where billions of dollars are moved from one country to another

with the click of a mouse. He offers not only an astonishingly

all-encompassing perspective on this globalized, Fast World but

also options for countries and companies who wish not only to

survive in it but also to thrive in it. He also explains how in

the globalized world a balance must be maintained between the

Lexus (the aspiration towards material prosperity) and the olive

tree (the ancient forces of culture, race, tradition and community).

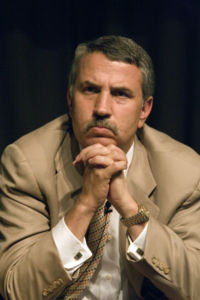

Thomas L. Friedman was for some years the foreign affairs columnist

for The New York Times, firing off reports as Beirut correspondent

and later winning a Pulitzer Prize for his book, From Beirut to

Jerusalem. In this new bestseller, Friedman explores an arena

much larger than geopolitics because it encompasses the globe

itself. He ventures to declare that globalization has become the

defining international system in the world today, replacing the

system put in place by the Cold War. In fact, he contrasts the

defining principles that distinguish the Cold War and globalization.

During the Cold War, there were two superpowers, each excluding

the other in its spheres of political and economic influence.

In the globalized world, the defining principle is not exclusion

but integration. The Internet is integrating the entire world.

Friedman says, “That’s why I define globalization

this way: it is the inevitable integration of markets, nation-states

and technologies to a degree never witnessed before – in

a way that is enabling individuals, corporations and nation-states

to reach around the world farther, faster, deeper and cheaper

than ever before and in a way that is enabling the world to reach

into individuals, corporations and nation-states farther, faster,

and deeper, cheaper than ever before.”

Globalization is a spawn of a free market economy. Its defining

measurement is speed. Friedman says the most frequently asked

question in a globalized world is, “How fast is your modem?”

In this system, the defining economists are Joseph Schumpeter,

the Austrian Minister of Finance and Harvard Business School Professor

and Intel Chairman, Andy Grove. Schumpeter wrote in his book,

Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy that the essence of capitalism

is the process of continuously destroying the old and less efficient

product or service and replacing it with new, more efficient ones.

Grove took this notion and popularized the idea that dramatic

industry-transforming innovations are taking place so fast that

only the paranoid, those who are constantly on the watch for these

innovations, can survive. In such a world there are no friends

or enemies, only competitors. Nothing is constant, not your job,

your community or your workplace, which can be threatened almost

overnight by new technological forces beyond your control.

Friedman thinks globalization is built around three balances,

which overlap and affect one another. There is the traditional

balance between nation-states, between nation states and global

markets and between individuals and nation-states. The balance

between nation-states still exists. In explaining the second balance,

between nation-states and global markets, Friedman describes the

millions of investors as the Electronic Herd, who move money around

the world with the click of a mouse and who center their activities

in such financial centers as Wall Street, Hong Kong, London and

Frankfurt, which he calls, “the Supermarkets”. Suharto's

downfall in 1998 in Indonesia is example of the Supermarkets'

clout. They withdrew their support for the Indonesian economy.

In the third balance, the one between individuals and nation-states,

the individual gains so much power that it can influence the decisions

of nation-states ...